Is it an injury or just marathon training?

Every marathon runner gets pain. The trick is knowing which aches are normal training fatigue and which ones mean stop before you do something stupid.

How to tell the difference between “normal marathon suffering” and an injury you should not ignore

The problem no one warns you about

Marathon training does not hurt in one dramatic, obvious way. It hurts quietly. Gradually. In ways that make you wonder whether you are injured, weak, or simply aging at an alarming rate.

One day your legs feel a bit heavy. Then stairs become an event. Then you find yourself doing a small diagnostic jog around the kitchen to see if today’s pain is “real” or just vibes.

This is where most runners get stuck. Is this an injury, or is this just marathon training slowly dismantling you? The trick is learning how to tell the difference before you do something heroic and stupid.

Why marathon training hurts in the first place

Before we talk about injuries, we need to talk about why marathon training causes pain even when nothing is technically “wrong.”

Fitness improves faster than your tissues

Your heart and lungs adapt quickly. Within weeks, your aerobic system gets better at delivering oxygen and clearing waste products, making you feel fitter. Your muscles adapt at a decent pace too; they get stronger and more efficient at producing force. Your tendons, ligaments, and connective tissue are the slow learners in the group.

Tendons remodel in response to load. That process is slow, metabolically expensive, and deeply uninterested in your training plan. When you increase mileage or intensity, muscles often cope first. Tendons complain later. This is why you may feel fitter and more broken at the same time.

Fatigue masks damage and exaggerates sensations

As training volume increases, fatigue accumulates, which changes how pain is perceived.

Small, harmless sensations feel dramatic when you’re tired, and at the same time, genuine tissue irritation can feel strangely manageable once you are warmed up. This is why so many runners say things like “It hurts until I start running, then it’s fine” which can be completely normal or deeply concerning depending on context.

Pain that is probably just marathon training

This is the background noise of marathon training: unpleasant, annoying, but usually not dangerous.

Dull, symmetrical soreness

- Both calves feel tight

- Both quads ache after long run

- Everything feels stiff (but not sharp)

These are usually a sign of muscular fatigue and connective tissue adaptation, not injury.

Pain that improves as you warm up

If the pain eases after 10 to 15 minutes and does not worsen during the run, that is usually stiffness rather than damage.

For example, achilles or calf tightness that fades once blood flow increases: stiffness is normal and the increase in temperature and circulation improve tissue elasticity and nerve tolerance, which is why it feels fine when you start moving

Important caveat: improving with warm-up does not mean you can ignore it indefinitely or pretend it isn’t happening. It means manage your load, monitor trends, and consider adding some cross-training like yoga including stretching and mobility.

Pain that appears after harder sessions or long runs

If soreness reliably shows up after long runs, hill sessions, or speed work and then settles within 24 to 48 hours, this is expected. Eccentric muscle loading causes delayed onset muscle soreness (or DOMS). It is unpleasant but normal and gets better with rest. Foam rolling feels intensely unpleasant and may or may not help, but it does make you feel like you’re doing something about it.

Pain that might be an injury

This is where runners should stop negotiating with themselves and pretending they are being “mentally tough”.

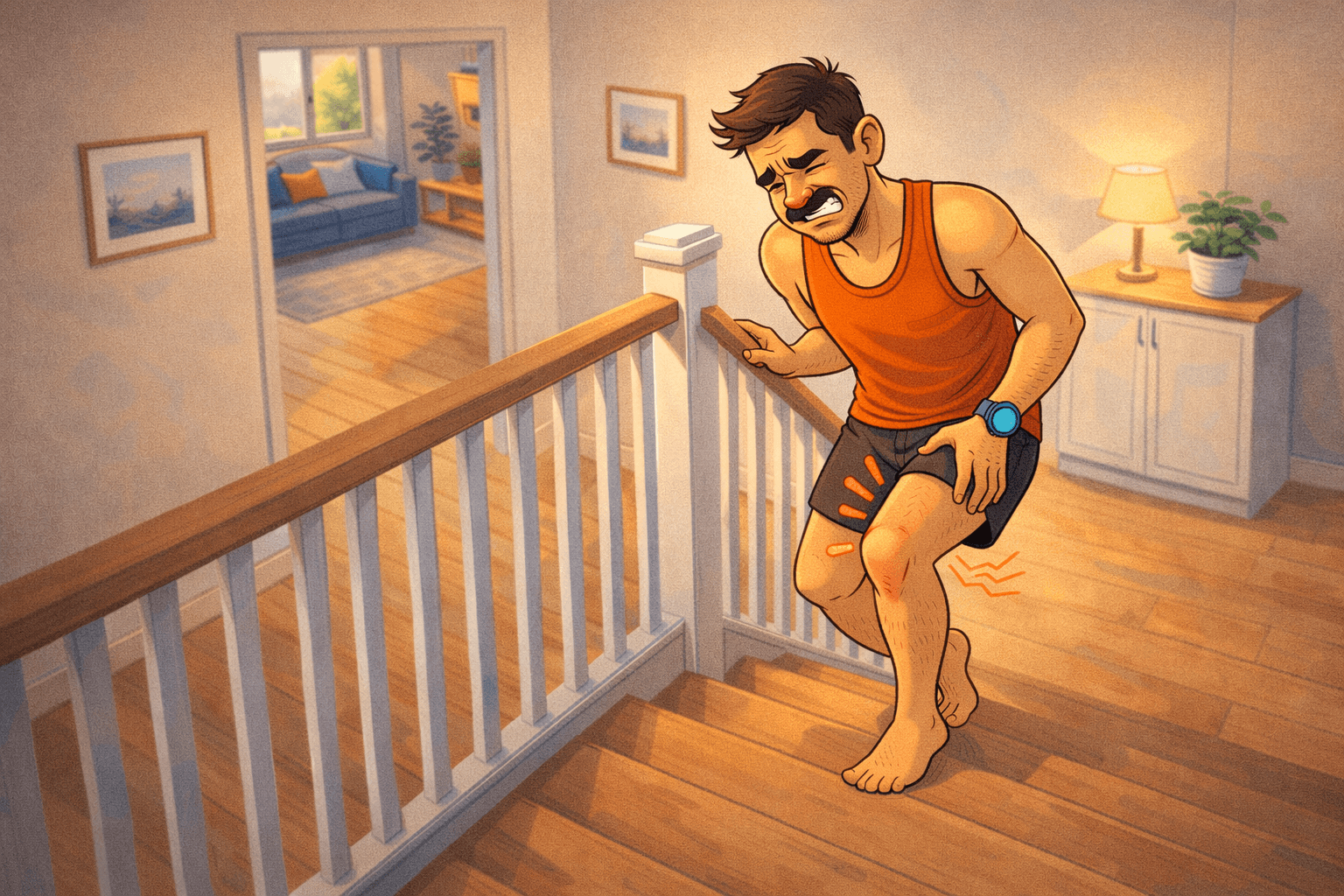

Sharp or stabbing pain

Pain that feels like a jab, pinch, or knife is rarely just fatigue. For example a sudden stabbing sensation in the lower quad when walking downstairs may suggest localised tissue stress, often at a tendon or muscle junction.

Pain that gets worse as the run goes on

If the pain escalates with each kilometre, especially at the same spot, pay attention. Knee pain that starts as a whisper and becomes a shout by the end of the run suggests the tissue is not tolerating stress.

Pain that changes your stride

If you are limping, shortening your stride, or subconsciously protecting one side, that is a red flag. Altered mechanics shift load elsewhere, meaning that if you keep running, your niggle will soon become three.

Pain that lingers or worsens over days

Normal training soreness fluctuates while injuries tend to escalate. If the pain is worse this week than last week despite similar training, that trend matters more than any single run.

The brutally honest self test

Ask yourself these questions without lying.

- Does this pain change how you run?

- Is it getting worse week to week?

- Would you tell a friend to stop running through this?

If you answer yes to any of those, you should reduce load and consider seeing a physio. It doesn’t mean stopping forever, but temporarily lowering volume or intensity allows tissue to catch up.

What to do when you are unsure

Do not panic rest

Stopping all activity at the first sign of discomfort often leads to stiffness, fear, and lost momentum. Instead, reduce volume by 20 to 30 percent, keep intensity low, and monitor symptoms.

Keep easy runs actually easy

Easy pace should feel boring. If your easy runs feel like work, your tissues are not recovering between sessions. Reducing intensity often reduces symptoms without stopping training.

Respect patterns, not single runs

One bad run means nothing. Three bad runs in a row means something. Track how pain behaves across days, not minutes.

Why this matters more in marathon training

Most marathon injuries are not caused by one bad session. They are caused by ignoring small signals for weeks because the plan said “long run.” Learning the difference between normal training pain and injury is not a weakness. It is a rare competence.

Marathon training is supposed to be uncomfortable, but it is not supposed to be reckless. Most aches are your body adapting. Some pains are warnings. The difference is rarely mysterious if you stop pretending not to notice it and actually pay attention.